Computer Science 282: Social Aspects of Games, Leisure, and Entertainment

Unit 1: Leisure and Society

Maureen Gardner wins heat two of Women’s 800m Hurdles, Olympic Games, London, 1948. Courtesy National Science and Media Museum. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nationalmediamuseum/7649948668/

In this unit, you will be doing some exercises that encourage you to think about what we mean by games and how games relate to and intersect with other leisure activities, recreational pursuits, hobbies, and pastimes. There will be some reading required and some active creative work, but most of this first unit is concerned with different ways of thinking about your own experience and understanding of the things that people do for recreation.

This is a long unit that provides a background to the field and that touches on many of the issues that will emerge in later units.

Learning Outcomes

At the end of this unit you should be able to

- distinguish between games and other leisure pursuits.

- identify what motivates people to play games.

- apply sociological theories to game playing.

- explain the value of social interaction in game playing.

- analyze games in terms of their social effects.

- identify game-like features in non-game systems.

- analyze the effects of game-like features in non-game systems.

- reflect on your own attitudes to games and leisure.

Key Concepts

Your reflections should show an understanding of these concepts:

sociology of leisure, social capital, social networks, modes of social engagement, gender and leisure, politics and leisure, collaboration and cooperation, serious games, gamification

Some Questions to Think About

In this unit we will be asking you to think about your own experience and relate that to academic and other work on the subject. Among the questions we will be asking you to grapple with are

- What are the differences between leisure, entertainment, recreation, and games?

- What is “free” time?

- What is a game?

- Why do we play games?

- What value do we seek in playing games with other people?

- How do our leisure activities affect our interactions with other people?

- What roles do other people play in our leisure activities?

- What do our leisure activities tell us about ourselves? How do our leisure activities affect our sense of identity?

- Can games serve a serious purpose?

Time

This unit is expected to take over 25% of the time allocated to the course. We think this means it would take at least 30 hours of work for an average student to get an average mark but your mileage may be quite different. It involves quite a lot of reading and some writing, but you will get to play games at the end of it!

Getting Started

The purpose of this activity is to encourage you to think about the nature of leisure and the role of other people in leisure pursuits. We hope that by the time you have completed this activity, you will be more confused and less sure about the answers than when you started.

As in most other units, there are going to be frequent occasions that we ask you to write in your learning journal. You might find it productive to keep your learning journal open in a separate browser window. Alternatively, you may wish to keep a document open in a word processor or text editor and paste it into your learning journal later. Whichever method you use, do make sure that you save your work regularly.

Unit 1 Learning Journal Template

You may copy the following headings into your Unit 1 learning journal to make it easier to organize your work in this unit. This provides the headings for the tasks to be completed to meet the minimum task requirements. You are both welcome and encouraged to create new subheadings and headings as needed.

Remember, the more evidence you supply of meeting the required outcomes, the more likely you will be to achieve success on this course, so don’t be afraid to add notes, comments, thoughts, and reflections that go beyond the basic requirements.

Task 1: What Does Leisure Mean to You?

Task 2: What Is Leisure?

Task 3: Reflecting on the Sociology of Leisure

Task 4: Comparison of Social Motivations in Games You Have Played

Task 5: Gamified Systems

Reflections on Unit 1

Further Reading

Task 1: What Does Leisure Mean to You? (about 1 hour)

This task is intended to situate the studies you are about to engage with in a relevant context: to help connect what you already know with what you are about to learn. We would like you to start thinking about the things that you do for fun, bearing in mind that not all activities done for fun actually are fun or, at least, not all the time.

This task is intended to situate the studies you are about to engage with in a relevant context: to help connect what you already know with what you are about to learn. We would like you to start thinking about the things that you do for fun, bearing in mind that not all activities done for fun actually are fun or, at least, not all the time.

In your learning journal, make a list of the leisure activities that you engage in. For now, do not worry too much about definitions. Just think about what you do in your free time (and, in the process, think about what “free time” might mean to you). As you make your list, think about

- How many of these activities are pleasurable? Are there any things that you do for “fun” that are not (always) fun?

- How many of those activities involve other people? Note that this involvement may be direct or indirect. For example, it is fairly obvious that team sports, multiplayer computer games, or going out to dinner with friends. The involvement of others may occur in different ways, however.

Write your answers in your learning journal for Unit 1, with a subtitle of “Task 1: What Leisure Means to Me.” We expect that you will probably write a few paragraphs about this, but probably not more than what would, if printed, amount to about an A4/letter-sized page.

If you do not want to share this with everyone that is fine—you are welcome to share it only with your tutor if some or all of the information is personal or confidential. If you wish to do this, you can create a sub-page of your Unit 1 learning journal with different permissions than that of the main page. See the Using Circles section of Using Athabasca Landing in Unit 0 for information on how to manage your privacy settings.

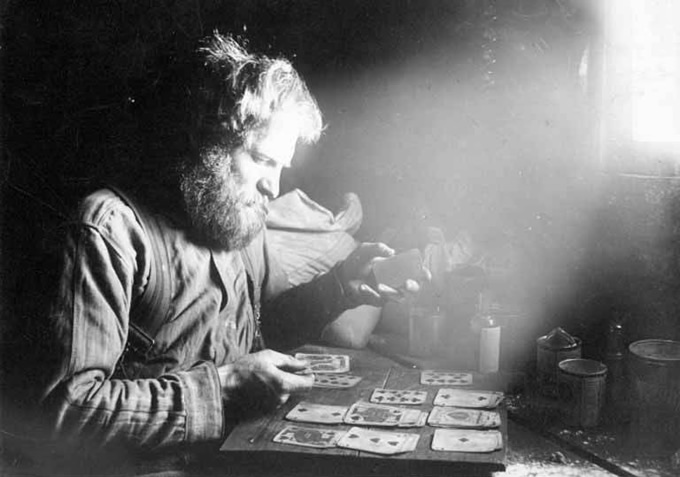

Charles Ainsworth playing cards inside cabin at 60 Above on Sulphur Creek, Yukon Territory, 1898. Courtesy University of Washington. https://www.flickr.com/photos/uw_digital_images/4476182073/

Task 2: What Is Leisure? (4–5 hr)

This task is intended to encourage you to reflect on some differences: the differences between work and play, the differences between games and play, the differences between leisure and play, the differences between playing and relaxing, and a whole lot more. We are hoping that by the time you have completed it, you will have some answers, but also, perhaps, see things as fuzzier and less certain than you saw them before.

This task is intended to encourage you to reflect on some differences: the differences between work and play, the differences between games and play, the differences between leisure and play, the differences between playing and relaxing, and a whole lot more. We are hoping that by the time you have completed it, you will have some answers, but also, perhaps, see things as fuzzier and less certain than you saw them before.

We are asking you to reflect on some questions in your Unit 1 learning journal. Use the subtitle “Task 2: What Is Leisure?” for this. You do not need to reflect in the same depth on every question, and we encourage you to add your own questions to this list. In many cases the answer will be “it depends”—this is good, but we would very much like you to think about what it depends on!

Consider whether or not the following are leisure pursuits, and think about the ways that others may or may not be involved in them:

- visiting a cinema (is it the same with friends or on your own?)

- writing a book (or writing a coursework assignment?)

- shopping (for a present? for your family’s food?)

- playing hockey

- watching hockey on TV

- watching hockey at a stadium

- playing hockey as a professional player

- going to a resort for a holiday

- going to a boot camp for a holiday

- filling in a crossword puzzle

- painting a picture

- doodling absent-mindedly

- jogging

- attending a wedding (or a funeral?)

- brushing your teeth (or applying perfume or makeup?)

- daydreaming

- gossiping

- repairing a car (or customizing a car with chrome fenders?)

- hiking (or walking to work?)

- swimming in a pool (or swimming as physiotherapy?)

- drinking beer (does it differ when done with friends and when done alone?)

- meditating or praying

- playing World of Warcraft

- engaging in a discussion about World of Warcraft on a dedicated site

- building a World of Warcraft mod

- being a professional computer game player

- developing a computer game in your spare time

- developing a computer game for profit

- playing in a band

- collecting playing cards

- fixing a broken Internet connection (fixing it for a friend?)

- taking a course at Athabasca University (or learning to drive?)

- Reading (does it make a difference if we are reading a set of instructions for a new washing machine or reading a comic novel?)

- chatting online (does it make a difference if we are chatting with friends or chatting with a technical support department?)

- visiting an art gallery

- playing with your children

- canvassing for a political party

- collecting for a charity

- participating in a fun run (or participating in a competitive marathon?)

- gardening (does it make a difference if you are growing flowers or growing vegetables to eat?)

- raising chickens to feed your family (or raising chickens as pets?)

- fixing a drain (or fixing a model airplane?)

- dating (would the answer be different for, say, speed-dating?)

- travelling (is this the same if it is to a holiday destination or to a work-related conference?)

- watching a rented video (Is this the same as watching a popular program on broadcast TV ? Does it make a difference if someone else is watching it with you? Why?)

- chopping wood

- washing dishes (with others?)

Feel free to add others to this list from the list that you made earlier.

Are these all leisure activities? If not, why not? Are any of these social activities? If not, why not? Are there any activities that involve no one else at all? What is the difference between (say) reading and writing from a social perspective? Is all writing the same? What about a personal journal? Is all reading the same? What effects to these activities have on us, and how do they affect our relationships with others?

Make notes of any thoughts you may have on this under the “Task 2: What Is Leisure?” heading in your Unit 1 journal. We do not expect or require you to make notes about every item on the list—just note those where you are not sure, or that are surprising, or puzzling, or interesting to think about. It may be particularly interesting to compare and contrast apparently similar examples. We expect in the region of a printed page or two of notes.

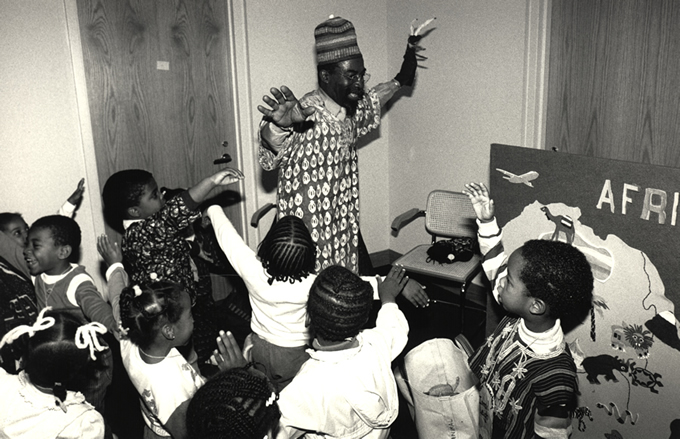

National Museum of African Art Docent James Brown, Jr., with Preschoolers. Photographer: Jeffrey Ploskona. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution. https://www.flickr.com/photos/smithsonian/8723822410/

Are Any of These Games?

What makes one thing a game and another thing not? Bernard Suits (2005) came up with a definition that you may find thought-provoking:

Playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.

While succinct and almost certainly true, might this apply to things in the list above that are not games? Others have gone for a more descriptive definition. In her book Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World Jane McGonigal suggests that all games share four defining traits:

- a goal

- rules

- a feedback system

- voluntary participation (more accurately, this might be thought of as knowing and intentional participation)

Can you think of any games to which this does not apply? Does this definition successfully discriminate between things that are unequivocally games and things on your list that may be on the borderline or in a different category of leisure pursuit altogether?

To gain a broader perspective and read some arguments that suggest a refinement of McGonigal’s ideas, read https://www.whatgamesare.com/2011/02/all-games-are-played-to-win-design.html in which Tadgh Kelly presents his own ideas and a critique of some of McGonigal’s arguments.

Write your thoughts in your Unit 1 learning journal, under the heading “Task 2: What is Leisure?”. We expect a couple of paragraphs of notes on this, but you may find you have more to write.

Task 3: Reflecting on the Sociology of Leisure (7–8 hr)

In your learning journal, write notes on this task using the subtitle “Task 3: Reflecting on the Sociology of Leisure.” Choose questions that interest you, and write your summary thoughts in a paragraph or two.

In your learning journal, write notes on this task using the subtitle “Task 3: Reflecting on the Sociology of Leisure.” Choose questions that interest you, and write your summary thoughts in a paragraph or two.

The study of the sociology of leisure grapples with, amongst other things, questions such as those you have just been addressing. The sociology of leisure is concerned with how we spend our free time, which raises immediate questions about what we mean by “free time.” It covers what are fairly unequivocally leisure activities such as sport, tourism, and games, but, as your answers to some of the questions above might reveal, even these have some decidedly blurry edges that at least make you think twice before deciding whether they are leisure activities or not.

Once you start to look at the activities at the edge, the term leisure becomes complex and hard to define. Is it simply a stretch of time when you are not working or engaged in obligatory activities such as housework? Can you engage in leisure pursuits at work? Can work be fun? If so, what makes it different from leisure? Are all leisure activities done for fun? Moreover, although many leisure activities explicitly involve performing them with or for others, some seem fairly solitary or only indirectly rely on the presence of others, but many straddle borders that are less clearly social, yet seem to have some socially oriented or socially mediated character. It seems that some pursuits change in quality when others are involved.

To help make more sense of this and to get a clearer idea of the wicked questions that are raised once we start to examine the issues more closely, please start by reading the Wikipedia article at https://en.wikipedia.org/

Having read this paper, would any of your answers to the questions at the start of this exercise change?

Which of the leisure pursuits described above or that you engage with might be described as autotelic? The word occurs in Wilson’s paper without further definition of discussion—for a definition, see https://en.wikipedia.org/

The paper uses the term Goffmanesque. To help understand this phrase, read https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erving_Goffman.

As this course progresses, we will be returning again to the work of Erving Goffman and what has been made of it, in particular as it relates to identity, framing, and dramaturgical analysis. To get a fair overview of the main ideas, this essay at http://gamestudies.org/1001/articles/wanenchak should provide you with sufficient background for this course and will come up again in a later unit.

The Value of the Social

There are lots of reasons that we do things with other people and lots of explanations for our social behaviour from a variety of perspectives. We will only be covering a subset of these in this course that are of particular significance when considering social aspects of games, but the fact that we have left out something else doesn’t mean that it is not important or relevant.

Background: The Effects of People on Others

As a species, we are innately social. Our intelligence is not so much to be found in individuals but in our ability to share and communicate with one another. Try to imagine how smart you might be without language, shared objects and technologies, writing, drawing, social infrastructures, and other essential aspects of human existence that involve distributed cognition.

Individual intelligence is only possible in the context of social engagement with others, whether directly or indirectly. The objects around us embody the intelligence of others, and almost everything we do not only relies on what we have learned through others but also in the embedded knowledge in our technologies, from handles on doors to aircraft safety systems. The most solitary and “technology-free” activities that we engage in are reliant on others, even if we are solitary hermits living the simplest life imaginable. Without the people who helped the hermit discover foods he or she can eat and identify harmful and non-harmful things, who established methods for meditation, who nurtured the hermit when he or she was growing up, who gave him or her the language and conceptual tools for thinking about the world, the hermit could not live that life at all.

For most of us, people continue to affect us in many ways. We are parts of many intricate social systems, being influenced by and influencing others. We do things with and for others for a wide diversity of reasons.

Altruism

There are good grounds to believe that altruism is an innate feature of all humans. Most of us do things for others, if only for our close friends or family, without expectation of any personal gain. However, this extends further: for instance, there are few of us who would not, given the opportunity and without great risk to ourselves, save a child from imminent danger. We do not do such things because of a calculation of the pleasure it will give us nor even the pain of not doing so, but as an automatic, innate response. While altruistic motives may not always be purely selfless, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that they are a part of our complex natures.

Personal Gain

Equally, there are good grounds to believe that we do things for personal gain (or for the benefit of people we are close to) and that, in most cases, this comes at a cost to others. It is very hard to engage at all with the world without having some impact, direct or indirect, on others. For example, driving a car or even riding a bicycle invariably involves some harm to others, if only due to the damage done to the environment in their manufacture and delivery to the store. Once we are in possession of them, we take up space and use up resources that often materially impact other people. Of course, they may come with benefits: we may use our car or bicycle to assist the economy by driving to work, as well as providing a source of income for those involved in building, transporting, selling, and maintaining it, for example. We therefore have to make ethical decisions all the time, making implicit or explicit judgements about the relative harm we cause against the benefits to us or to those around us.

Boy Scouts - Gettysburg 1913 July. Courtesy The Library of Congress. https://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/3931075949/

Power

Others contribute in an indefinitely large number of ways to our ability to control and influence the world. In some cases, such as presidents and industry chiefs, this is self-evident and a common part of the motivation for aspiring to such a role. Power can play an important role in games—many involve overpowering others, for example.

However, it is not all a question of power struggle: we are all empowered by one another. The fact that someone has kept and milked cows, put the milk into cartons, designed and built refrigerators, created and maintained distribution networks, run grocery stores, maintained a financial system and a host of other roles gives us the power to have a glass of milk when we want one.

Social systems, including economic systems, regulatory frameworks, technologies, management systems, scientific research and much, much more are what make human life not only possible but comfortable and controllable. Many games take advantage of our innate ability to empower one another and help others, whether or not for altruistic reasons.

Status

Our social systems are deeply entwined with social status and, for many people, this is an end in and of itself, as something quite separate from issues of power or gain. This may be very blatant, and provide us with power over others and our environment: from politics to company hierarchies, there are some deeply embedded hierarchies in which status is not just a source of personal satisfaction in itself but comes with material benefits and power to control more of our lives. Winning a game may often confer status, whether transient of not. However, status also relates to how others perceive us, the benefits that we may gain from them, and those that they gain from us. This leads to the notion of social capital.

Social Capital

The concept of social capital is concerned with the reciprocal ties that allow us to make use of our social connections with others and for them to make use of their ties to us in order to achieve some personal or mutual benefit. It is distinct from financial capital (money) and human capital (people and their abilities to do things).

Read the Wikipedia article at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_capital.

Putnam, in Bowling Alone, made a popular distinction between bonding and bridging social capital, relating to the concept introduced by Mark Granovetter of strong and weak social ties. Sometimes our social capital is concerned with sustaining close relationships, sometimes with making connections with others beyond our immediate close-knit groups. Does social capital require someone to be who they say they are? See https://old.gigaom.com/2011/09/16/why-twitter-doesnt-care-what-your-real-name-is/ for a discussion of whether or not this is the case.

Games Have a Social Context

Social game playing is, of course, deeply dependent on the presence of others, and our interactions and behaviours in social games are part of the way they work. While the social dynamics may be in microcosm, simulated in a safe space and one step removed from our engagement in the “real” world, many of the same factors play a role in making the game enjoyable.

However, even non-social games are part of our social context. They affect us in ways that impact the rest of our lives and, consequently, the people around us. It remains a highly contentious issue as to how and in what ways they do this (to be covered in a later unit) but it is undeniable that playing games changes us in some ways, for better or for worse. At the very least, it takes time away from other things we might be doing. We know that this can be very harmful. There have been a few very extreme cases such as that of a couple playing a game that involved bringing up a virtual child to such an extent that they neglected their real child, who starved to death as a result. This is sadly not the only case of this nature. From deaths caused by spending too much time playing games—https://www.christianpost.com/

The Difference Between Two People and Three

Many games are played by pairs of individuals, or dyads. There are some fundamental differences between such games and those played with more people. Three people can form coalitions, with two ganging up on one. If one person leaves a dyad, there is no social interaction left, no community, but if three people are there and one leaves, the community persists.

This scales up with numbers of people. Beyond a certain size, communities become too large for any one individual to know every other within them. At this point, the usual way forward is for the community to subdivide into smaller groups and clusters. The precise point where this happens varies considerably, but there is some evidence to suggest that it tends to happen at around Dunbar’s Number, or about 150 individuals. Dunbar came up with this number by extrapolating from brain sizes and sizes of community among other apes, but it appears to hold moderately well in a human setting. Dunbar’s number is roughly the size of the average pre-industrial tribe or village, for example.

Think of the communities that you are a part of. Are any of them larger than Dunbar’s Number? Most people, for instance, live in villages, towns, or cities that are considerably larger than that, and many of us are parts of companies, schools, organizations, and societies that are much bigger. If so, are they subdivided in any way? How are they organized so that you do not need to know everyone in them for them to function effectively?

Different Social Forms

One of the most commonplace and powerful ways used to overcome the limitations imposed by Dunbar’s Number is to form groups. Groups are subdivisions of communities that typically have a purpose. Groups tend to have hierarchies and roles. They tend to have rules (explicit or implicit) and rituals for joining and leaving, often with some barrier to entry. Groups tend to be cohesive, tend to rely a lot on bonding social capital to sustain them. They have an existence beyond the individuals that are part of them. Groups include things like families, clubs, teams, classes, societies, and companies.

Rainie and Wellman (2012) and others have observed that, while many social activities are performed in groups, many of our interactions focus around our individual networks. Networks are formed from our connections with one another—our friends, co-workers, people in our neighbourhood, people we connect with online, and so on. They don’t normally have distinct boundaries, rules, or expectations of particular behaviours although memes and norms can spread through them.

There is some evidence, for example, to suggest that networks can influence whether we smoke, are obese, or are happy. Networks may occur within groups but, nearly always, cut through and spread beyond them. Networks are characterised by both bonding and bridging social capital. Through our networked connections, we are seldom more than six links away from anyone else on the planet, as Milgram’s famous “six degrees of separation” experiment showed and that has since been largely verified by others (Watts, 2004).

Trust and Reputation

In any sustained interactions with others, we need to learn to trust them. Trust may be thought of as a reasonable expectation that someone will not behave maliciously or unkindly towards you. Before we get to know them, we pick up cues, often from others who know them, marks of status, or our previous experiences in similar situations, which we use to judge whether or not they are trustworthy.

In most social situations, we develop reputations: ways that other people perceive us that allow others to judge whether and how we may be trusted. Sometimes, reputations can bleed from one field to another. For example, the phrase “trust me, I’m a doctor” typically suggests not only a simple ability to administer medication and make diagnoses, but also a range of ethical, professional, and social facets of the person making that assertion.

Why do people play together?

While there are many generic aspects of any social activity, some are distinctive to the context of playing. Play is a central part of almost everyone’s childhood and, for most of us, continues in to adulthood. We are not alone in the animal kingdom in playing although, unlike most other creatures, we often invent rules, procedures, and methods of play that make our games quite distinct from those played by puppies, chimpanzees, kittens, and foals.

While animal games may have goals, perhaps some implicit rules of conduct (no biting, for instance), certainly some feedback system that helps identify success and voluntary participation, the explicit rules of human games make them a more constraining kind of activity than any animal games. Although we do quite frequently play alone, much of the time we play with or against others. More often than not, play is a social activity. Other people often make games more interesting, engaging and challenging.

Review https://www.whatgamesare.com/2011/02/all-games-are-played-to-win-design.html, an article you read earlier about what “winning” means in the context of games. Note that it is not about points! For a similar take on the issue, see also https://techcrunch.com/2012/11/17/everything-youll-ever-need-to-know-about-gamification/ by the same author. There are some useful concepts and ideas in these articles that will help you to frame your thinking throughout this course, including the concept of a ludeme—a method, technology, or feature in games that spreads across multiple games, often inappropriately and divorced from its original context.

Waterfront workers play ‘warri’ - a game of African origin - during spare moments on the jetty at Bridgetown. 1955. Courtesy The National Archives UK. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nationalarchives/8022854127/

Task 4: Comparison of Social Motivations in Games You Have Played (3–4 hr)

For the following exercise, write in your learning journal for Unit 1 using the heading “Task 4: Comparison of Social Motivations.” We are expecting something in the region of a page of text, were it printed on A4/letter paper.

For the following exercise, write in your learning journal for Unit 1 using the heading “Task 4: Comparison of Social Motivations.” We are expecting something in the region of a page of text, were it printed on A4/letter paper.

Think about games that you have played, whether recently or as a child. Why did you do it? What were the motivations? Were they always enjoyable? What did you get out of them?

Think about games that you have played involving other people. These do not have to be computer games although in the context of the course, it would be a more useful exercise if they were.

- Choose two of these games that are as different as possible.

- For each, describe the kinds of interactions within them and the ways that people engage with one another within and around the game.

- Next, try to identify the social motivations behind playing them.

We are not interested in in all the ludic facets of the game, only those that that relate to the social engagement within or caused by the game. Things like the puzzle solving, thrill seeking, or entertainment aspects are only relevant to this task if they contribute materially to the social effects of the game.

Note that not all social activities that relate to games may be found in the gameplay itself. For example, as any chess player will attest, there is often a spoken or unspoken dialogue between players that is quite separate from what happens on the board itself. In quite a different way, guilds, clans, and other social forms that crop up in or around MMORPGs are often an important part of being a game player, in some cases becoming more significant to people’s lives, especially in terms of social capital, membership of supportive groups, and as a means of defining social identity, than the game itself.

On the Edges of Gaming

Background

We have already encountered some game-like systems that do not fit neatly into the game category. Now we will be looking further into ways that games or game-like functionality can be used to gamify a range of social activities such as education, shopping, dating, and online discussions, and the good and bad consequences of doing so. We will be dwelling on those borders, thinking about where they lie and examining things that straddle them or are near them.

We will, amongst other things, be looking at serious games (typically used for education and training), immersive worlds, rating sites, and uses of game-like devices such as points and badges in other contexts. We hope that as you read this and perform the task associated with it, you will gain a more refined notion of what makes something a game, as well as some of the social dynamics and motivations behind game playing.

Gamification

The concept of gamification describes the use of common gaming mechanisms—ranging from the awarding of points to puzzle solving, from deliberate use of game engines in education to game-like rules in social gatherings—in contexts other than things that are explicitly labelled as games. This has been widely used in educational settings, but also in a variety of settings from shopping to dating.

Read https://blog.codinghorror.com/the-gamification/ for a discussion of how the developers of Stack Exchange borrowed ideas from computer games to make the site more attractive, usable, and helpful. From the same site, also read https://blog.codinghorror.com/the-worlds-largest-mmorpg-youre-playing-it-right-now/, which takes a broader view of most online interactions as being participation in a form of a massive role-playing game. Do you agree with the author’s arguments and opinions? Now read https://techcrunch.com/2012/11/17/everything-youll-ever-need-to-know-about-gamification/, which provides a practical perspective from the point of view of a system designer and highlights some of the pitfalls and errors commonly made when gamifying an activity.

Likes, Luvs, and Plus-ones

Many systems make use of game-like points systems that attempt to foster greater activity and networking among users of sites. Facebook Likes, Google Plus-ones, and Bebo Luvs, for example, in many ways resemble the scoring systems of some games, with rewards being given for posting something interesting. Of course, they have other purposes too, most notably in helping people to find high-quality content but also to encourage interactions, build social capital, and foster reciprocity.

There is, however, a potentially harmful flip side to such gamification. As in the case of gambling, the joy of the activity itself can become secondary to the desire to gain “points.” In a game, the gaining of points is intimately aligned with the gaming activity itself—they are the signal of success, not just of getting points, but of doing well at the game. It is built into the rules. If a game is well designed, it cannot be gamed: points are a direct and unequivocal measure of success.

Life, however, does not have such simple rules, for the most part. There are infinite possible reasons for someone “liking” something in Facebook, and no simple rules that equate a Like with any particular quality of an action or activity. Likes, Plus-one’s, and similar points systems may therefore become extrinsic to the system, the equivalent of giving financial rewards or cookies for “good” behaviour, made worse by the fact that there are seldom any easy ways to know what it was about the behaviour that is considered to be good.

Self-determination theory and a host of experiments going back over many decades conclusively show the ill effects of extrinsic motivation. The pleasure of doing something is replaced with the immediate gratification of the reward (or punishment). The greater the extrinsic motivation, the less the intrinsic motivation (Kohn, 1999).

Karma and Badges

Though superficially similar to Likes and Plus-Ones, and often used in almost identical ways, systems employing karma points and badges sometimes operate in quite a different way. The general mechanism behind most modern systems that use karma points was developed in the Slashdot system of the 1990s, which persists to this day. Karma is awarded for doing things identified by the system’s designers as “good.” This includes many different things such as posting messages, responding to conversations, logging in, reading pages, direct ratings from others of an individual or an individual’s posts, length of membership, and many other more or less fine-grained actions. The number of karma points varies according to the action and is usually tuneable by the system administrator.

Some systems provide weightings that allow the rankings of those providing ratings to count for more or less depending on their own karma rating. Badges are often used as visible manifestations of similar point-based processes as well being awarded for things like gaining competence or skills in tutorials and quizzes. What makes these differ from simpler Likes and Plus-ones is that the motivation to gain points or badges is intrinsically bound to the activity for which they are awarded. Notice how this more closely equates with the nature of points awarded in games, where points are a signal of competence: they cannot be gained without successfully displaying the skill that they relate to.

Games Without a Purpose

There are many game-like spaces that are not games. This is notably true of various forms of virtual reality, up to and including many of today’s immersive worlds. Some of the earliest virtual environments that developed from the 1960s onwards, starting with MUDs (multi-user dungeons, reflecting their origins in Dungeons and Dragons games) and later MOOs (MUD-object-oriented) as well as exotic cousins like MUSHs (multi-user shared hallucinations) were inhabited spaces, created in text descriptions by their inhabitants. The MOO described in “A Rape in Cyberspace,” which we will examine in Unit 2, gives some idea of the richness, involvement, and imaginative engagement that these systems engendered.

Although some stayed with their origins and were used as creative gaming spaces, many were inhabited and built for quite different reasons, sustaining complex online communities in days when the fastest modems battled to reach 300bps and text appeared on the screen a line or even a character at a time.

Meanwhile, starting in the 1980s and developing throughout the 1990s, graphical virtual reality systems moved from simple, crude individual simulacra of lonely geometric spaces to become rich and vibrant immersive worlds, inhabited by other people and filled with recognizable objects. Resembling and often employing technologies used in multi-player games, systems that were developed in the 1990s and early 2000s such as ActiveWorlds and Habbo Hotel captured the imaginations of millions who entered these strangely familiar yet oddly different inhabited representations of physical space.

But their use remained a niche activity undertaken by those with the fastest of computers on the speediest of connections until the advent of Second Life, the first massively successful immersive world, which emerged at a time when computer and network power could (just about) cope with the demands of 3D rendering and multiple simultaneous connections. Even so, the power of computers and networks could barely handle the complexity, and it took a great deal of learning and skill to even move in this space, let alone to interact effectively. As the novelty wore off, disillusion with the limitations of the technology set in. While it was possible to interact with people in something resembling a physical space, and some objects could be used and manipulated in interesting ways, the 3D world of Second Life was and is not even a close approximation of the physical world.

In many ways, interactions with objects and locations are a very thin veneer on top of very much the same kind of techniques and technologies that underpin MOOs. Very few traces reveal the passage of others, apart from world builders, through this space. Most objects are static and immutable, or programmed to behave in very simple ways. Picking an object up seldom even moves it, no one leaves footprints and even simple things like collision detection are buggy and poorly implemented. Although some attempts have been made to program game-like behaviour into the environment, and some ingenious game-like features have been implemented on top of it, it is a very poor environment for games developers. It is a game-like environment without the rules and goals that make games distinctive.

Games with a Purpose

See https://www.good.is/articles/five-ways-that-games-are-more-than-just-fun for a few ways that games have been and can be used for more “serious” purposes than simply playing. You may want to think about what “serious” means in this context. Can play be serious? Read about serious games in Wikipedia.

Games That Do Good

Among the more intriguing genres of social game that have been developed over recent years are those that involve virtually no social engagement with others at all and yet which rely on a crowd of individuals to sustain them. Foldit (http://fold.it/portal/), for example, is a crowd-sourced gamification approach to finding interesting proteins that requires players to put proteins together with high scores relating to the chance that these might be interesting structures worthy of investigation by biochemists, who collect high-scoring configurations and test their applicability in real-world settings.

A similar approach is taken by EteRNA (http://eterna.cmu.edu/web/ ) as a means of discovering useful patterns for synthetic RNA. Stemming from crowdsourced approaches like Rosetta@Home and SETI@Home, grid computing applications that simply rely on many people dedicating some of their processor cycles, typically while a screensaver is running, such methods use the creative and cognitive powers of real human beings rather than raw PFLOPs (peta-floating-point-operations-per-second) to solve complex problems. Games are used both as a motivating instrument and as a tool in which the gameplay itself provides the information needed by researchers.

Are these social games? There are often some ways that social capital is designed to play a role, such as halls of fame and the use of points and badges that may be shared with others. However, this is little more than was seen in the earliest arcade games and is relatively rarely the main motivation for players to engage with these games. There is an important sense in which these kinds of games are played with others, inasmuch as they would be virtually useless were it not that many people are playing them. However, they seldom provide more than the minimum of interaction between players: they are games in which people cooperate towards a common goal, but do not collaborate. They do not normally work together, but the sum of their individual contributions can make a big difference.

A more direct social relationship between social gameplay and real-world benefits can be seen in games like Lil’ Green Patch or the use of “sugar beets” in Farmville, wherein in-game activities are used to make money for worthy causes. This approach makes considerably more use of the social element of the game due to the strong association with social capital that such games play on. Unfortunately, such games have often been plagued by concerns of scamming, as the success of early examples of the genre led to copies that directed little or no money to the causes they claimed to support.

Gamification can, of course, do good for companies, often playing roles in marketing strategies. See http://www.aweber.com/blog/email-marketing/easy-gamification-examples.htm for some simple examples.

Edutainment and Serious Games

Educators have long been intrigued by games. Gamers learn complicated, often mind-bending, physically difficult or taxing processes, solving problems and overcoming difficulties with a very high level of dedication and motivation. Seeing this, many teachers compare this enthusiastic and effective learning with what goes on in their own classrooms and wonder whether they can be used to improve their own teaching. Many have tried, often with high levels of success although the wealth of dire “educational” games found in schools shows that success is far from guaranteed and the hype is often misplaced. For example, this large-scale study revealed little or no evidence of performance improvements resulting from the use of one set of popular mathematical games.

It is hard and usually a very time-consuming expensive task to make a compelling game. Most commercial titles fail to meet that goal, and it is unsurprising that the same is true of most educational offerings. More than that, it is very important that the kinds of tasks and problems afforded by a game be very closely aligned with the learning that they are intended to bring about. Educators do not normally wish to teach gaming skills: they want to teach life skills. The constructive alignment of game skills with life skills is a complex and difficult task for even skilled educators to achieve.

There are many opportunities for social games and game-like systems to improve learning in ways that go beyond what a single-player game can achieve. Some of this is simply because the presence of others can be used to help teach teamwork and social skills. This does not relate only to the game itself but also to the metagame. Some of the value lies in the human ability make decisions that are hard to program into a game—humans can judge softer skills, offer advice and help, and adapt to different learner needs more easily than can be programmed into a machine, at least for non-trivial learning tasks.

See http://www.lostgarden.com/2008/06/what-actitivies-that-can-be-turned-into.html for an interesting discussion of what can and what cannot be gamified for educational purposes. Do you agree? Can you think of any counterexamples or ways that only some of the criteria for gamification are needed?

Art Games

Games as art, as opposed to art in games, have quite a long history. Follow links from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_game to explore some of the ways that games have been presented as art forms. One of the most intriguing ways that many of these differ from more conventional art forms lies in the role of the viewer as a performer and often a contributor to the art work. In many cases, the gameplay is a contributor to the purpose of the work, but the work is the end rather than the game itself.

Things That Are Not Quite Games

MOOCs

Massive open online courses, as the similarity of the name to MMORPGs suggests, are courses taken by a large number of people in an online environment. Most do not lead to any usable qualification although most award some kind of certificate of completion and marks for work done on the course. They are thus typically taken for fun as a leisure pursuit. Among the features that many share are schedules and targets, formative feedback quizzes, and a set of expectations, norms, and rules about how people should behave within them.

Are MOOCs games? If so, why? If not , why not? Remember McGonigal suggests that games should normally have goals, rules, a feedback system, and voluntary participation and, on the face of it, these conditions seem to be met. However, the fact that MOOCs have a purpose beyond the game itself makes them a little different. Suits’s definition of a game being a voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles seems to apply here. People engage in a MOOC at least partly in order to learn something of value to them and, in many cases, the obstacles that must be overcome are (we hope) necessary. Success in a MOOC is at least partly to have learned what one sought to learn.

American soldiers gambling in Brisbane, 1943. Courtesy State Library Queensland. https://www.flickr.com/photos/statelibraryqueensland/4924975051/

Online Gambling

You may have already come across gambling games in your explorations of different gaming systems. They occupy an unusual position in gaming inasmuch as the game itself is, to some extent, a means to a further end: losing money. However, it is notable that a lot of the extra value that some add to the process is the fun of losing money to real people rather than simply a machine. How, if at all, does this differ from the case of MOOCs? Both appear to have game-like elements and both are focused on an outcome beyond the game itself.

Online Shopping

While it would be hard to classify most online shopping sites as games, some contain gamifications of the process, most notably in ratings systems. Some, such as Amazon or Netflix, make use of collaborative filters that require you to explicitly rate items and, as a result, they make recommendations based on what other people who liked the same kinds of thing also liked.

In itself, this is not a game-like system, but the effects on behaviour can turn it into one. The phenomenon has been observed in people changing their patterns of viewing in TiVo systems or rating books differently in order to prevent embarrassing or inappropriate recommendations. In effect, people are playing a game with the recommender system, which has its own rules and provides immediate feedback.

Social Media as Games

For many people, the use of social media such as Twitter, Facebook, Google+, or YouTube can be viewed as a leisure pursuit, though there may be many other reasons for using them—discovering news and information, building connections for career advancement, study, and so on. In many cases, they may be platforms for things that are unequivocally games—Farmville, Happy Farm, Mob Wars, Pandemic, and many others are part of this genre.

They may also make use of ludic elements like karma points and other rewards for activities. It is possible to use game theory to explain interactions in social networks although this does not directly relate to playing games as such. However, are the sites or the ways that they are used games in themselves? Think about the kind of criteria we have been using so far to define games. Do any apply? Are there any situations or ways of using social media in which all apply?

Online Dating

There is a tradition of treating courtship rituals as a game—in literature, film, nature programs, and popular psychology books—but such uses of the term tend to be more metaphorical than literal. Nevertheless, many online dating sites do gamify the process of finding a partner, establishing rules, rating scales, a feedback system, and a clear set of goals. Are these games?

Rating Sites

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Review_site#Rating_site for a description of the rating site genre.

Sites such as Hot or Not, RateMyProfessors, and Kittenwars gamify the process of comparative rating. While some such as RateMyProfessors may serve a useful function as recommender systems, and people may take ratings from Hot or Not quite seriously, most of such sites are more for fun and distraction than to serve any useful purpose. Do you think these are games? They certainly appear to have some game-like elements: there are simple rules, there is an element of competition, there is interaction, sometimes there may be a need for skill. Are they games? If so, why? If not, why not?

Alternative/Alternate Realities

The genre of the alternate reality game (ARG) is both inspired by and inspires a range of gamifications of real-world interactions. Alternate reality games make use of a combination of the real world and online tools and systems. Typically, while there is a general game plan and rules like a conventional game, ARG designers play an active role, reacting to what people do in the real world, developing the plot and the actions in the games, directing the process and monitoring what people do through their online interactions.

It is normal for both real-life and online communities and networks to develop around these games, with collaborative and cooperative problem solving as well as competition. Most popular examples of the genre tend to run for a fixed period, either timed or dependent upon problems being solved. Examples include Perplex City and Find 815, a game that was linked in with and used to promote the TV show Lost.

Currently, among the more popular and persistent though possibly more mundane of these alternate reality universes that is part game, part social network, is Foursquare. Foursquare is a location-based social networking system where virtual space and meatspace collide. Using cellphones or tablets, individuals can lay claim to geographical locations as becoming the “mayor” of those spaces. Taking this a little further, there are a number of games played using a social network platform that make use of real-time events in the real world to inform and direct gameplay—for example, Mafia Wars and LifeSocialGame interconnect the game and real life in interesting ways.

You may find many examples of ARGs at https://www.argn.com/—we encourage you to explore and investigate this genre, thinking about the ways such games differ from other computer games that you are familiar with and what they share in common.

Geocaching

Geocaching is a popular pursuit that lies somewhere between alternate reality and, well—reality. If you have never hunted for a geocache, get hold of a GPS unit or GPS-equipped cellphone and try it—it’s fun! What struck me the first time I participated in a hunt for a geocache was both the physical game element—it is a great way to explore your neighbourhood—and the intense sense of physical connection with previous geocachers when we found the cache, a small box hidden in a garden on a traffic island in a big city. While the pursuit itself is a game that is often played cooperatively with others and there is a competitive element around the virtual community, the objects hidden in geocaches are social objects, a means of largely nonverbal communication.

Read https://0-doi-org.aupac.lib.athabascau.ca/10.1145/1357054.1357239 in the AU library to discover more about the motivations and practices of geocaching.

Augmented Reality

Distinct from, but related to, alternate reality systems is the field of augmented reality, wherein computers are used to overlay virtual information onto real-world contexts. Augmented reality has been a long time coming but has, for several years, been available through cellphones and portable games consoles, allowing virtual objects and information to be overlaid on images of the real world in real time.

In a less obvious way, the use of location-based information for virtual tours of things like public gardens and museums that overlay a soundtrack relevant to the surroundings provide a similar functionality. Less spectacularly but widespread, cellphone applications like Yelp or Urban Spoon provide local information about things like venues, cafes, bars, and restaurants with ratings and reviews supplied by former visitors. Augmented reality games have been played for several years, including variations on Tron played in real city streets, shoot-em-up games played in open spaces and inside Ingress, Google’s new augmented-reality game. The spread of technologies such as Google Glass is bringing such augmented reality gamifications of the real world into sharper relief.

Task 5: Gamified Systems (about 5–6 hr)

We would like you to identify two different game-like systems or games that have a purpose beyond the game itself, such as serious games or edutainment systems. Write this in your learning journal for Unit 1 under the heading “Task 5: Gamified Systems.”

We would like you to identify two different game-like systems or games that have a purpose beyond the game itself, such as serious games or edutainment systems. Write this in your learning journal for Unit 1 under the heading “Task 5: Gamified Systems.”

Using a combination of direct observation or experience and appropriate academic or other literature, we would like you to compare and contrast the game-like features in these systems, explaining what makes them game-like and why they are not purely games. We would particularly like you to focus on this as the big outcome for the task: clarify for your own benefit what makes something a game.

Critically analyze the ways that these systems use their game-like features, drawing attention to what works, what does not, how they might be improved, the unwanted side effects, the potential effects that they might have on out-of-game behaviour, and so on. We would particularly like you to focus on how appropriate the game-like features are in affecting people’s behaviour, in what ways they motivate as well as how they might demotivate people (if this is an issue) and especially, what things they motivate people to do.

Bonus Task: Play! (as long as you like)

Find a social game or game-like activity (e.g., a visit to Second Life or a session interacting with others on a social networking site) that you would like to engage with. This could be anything game-like at all, as long as there is some social element to it, including playing with kids or playing cards with friends but, as always, it is better that you choose something that relies on digital technologies, as that is the emphasis of the course.

Find a social game or game-like activity (e.g., a visit to Second Life or a session interacting with others on a social networking site) that you would like to engage with. This could be anything game-like at all, as long as there is some social element to it, including playing with kids or playing cards with friends but, as always, it is better that you choose something that relies on digital technologies, as that is the emphasis of the course.

As you play, think about what you are doing. Reflect on it in the context of what you have been reading and doing so far in this unit. Make a note (mental or otherwise) of things that you notice that were not covered in the earlier work you did for this unit. We would like you to discuss your findings in your reflections for the learning journal for Unit 1.

Reflections on Unit 1 (2–3 hr)

As for every unit in this course, write reflections on the process in a section of your learning journal for this unit with the title “Reflections.” Make sure that you have thought about all of the activities for this unit in your reflections. We do not expect that you will have the same amount to say on every activity, and we are in many ways more interested in how you make connections and synthesize your thoughts than in your detailed thoughts on the activities themselves.

As for every unit in this course, write reflections on the process in a section of your learning journal for this unit with the title “Reflections.” Make sure that you have thought about all of the activities for this unit in your reflections. We do not expect that you will have the same amount to say on every activity, and we are in many ways more interested in how you make connections and synthesize your thoughts than in your detailed thoughts on the activities themselves.

Think about the questions with which this unit began and how your ideas about the answers have changed or refined as you have worked through the tasks. Do not simply tell us what you did: we want to know how it mattered to you, and how it has changed how you will think about such things in future. Remember the mantra: What? So what? Now what? when writing your reflections. We are interested in what you did, what it meant to you, and how it has affected how you will think or behave in the future.

Optional Formative Feedback (1–2 hr)

If you would like to receive feedback on your work for this unit, first collate it into a portfolio (as a single wiki page) that maps what you have done to any relevant learning outcomes, using the template provided at the beginning of Unit 1. Submit a link to your portfolio page for the unit to your tutor via the Unit 1 Formative Assessment link on the Moodle home page.

Your tutor will provide brief feedback and may make suggestions for improvement if needed. Note that this carries no marks towards your final grade, and the tutor will not provide you with a grade for this at all. It is purely intended to help you to know how you are doing as part of the learning process. Although this involves extra effort on your part, we think that the process of collating the portfolio is valuable as a learning activity, and this provides useful practice for a task you will have to perform at the end of the course anyway.

References and Further Reading

Bryce, J., & Rutter, J. (2003). Gender dynamics and the social and spatial organization of computer gaming. Leisure Studies, 22, 1–15.

Paper on gender dynamics and online gaming.

Dunbar, R.I.M. (1993). Coevolution of neocortical size, group size and language in humans. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 16(4), 681–693.

Dunbar’s original paper in which he identified the maximum size for human groups.

Kohn, A. (1999). Punished by rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes (Kindle ed.): Mariner Books.

Rainie, L., & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked (Kindle ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts, US: MIT Press.

Book on networks and groups in the Internet age.

Suits, B., & Hurka, T. (2005). The grasshopper: Games, life and utopia: Broadview Press.

Watts, D. (2004). Six degrees: The science of a connected age. Norton: New York.

https://janemcgonigal.com/learn-me/: Jane McGonigal’s research writings—lots of provocative and interesting ideas presented here about ways of seeing life as a series of games as well as analyses of game dynamics and applications of gaming to real-world problems.

Most work by Erving Goffman. Of particular relevance to the study of social aspects of gaming are his books The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1956), Strategic Interaction (1969), Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience (1974), and Forms of Talk (1981). We don’t expect you to read any or all of these but, if this interests you, you may wish to explore them further.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Sociological_theories: Lists sociological theories found on Wikipedia. Around 200 are listed, but this is an incomplete list, and the articles themselves often link to further topics and areas that are relevant.

http://gamedesigntools.blogspot.com/2010/05/game-design-paradigms.html: Game design patterns and paradigms. Contains links to a wide diversity of resources and writings about the kinds of games that people play.